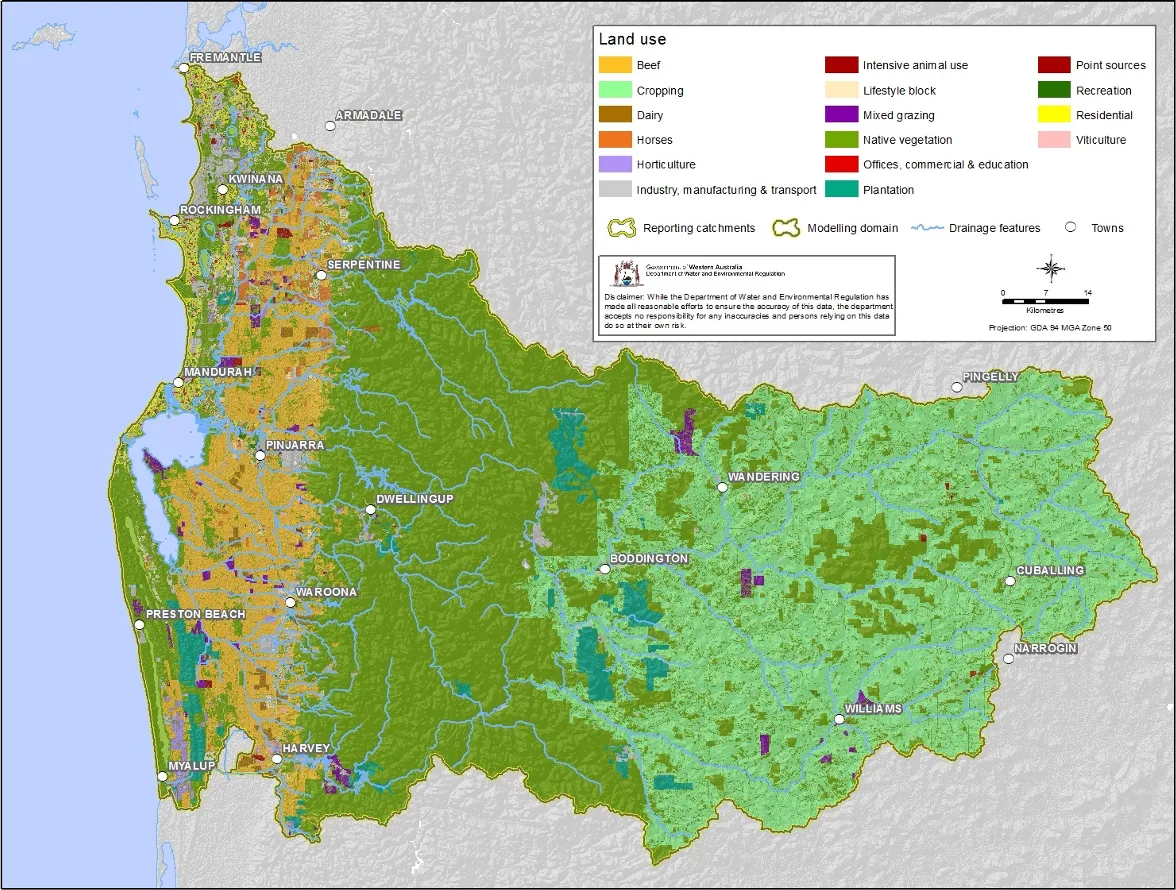

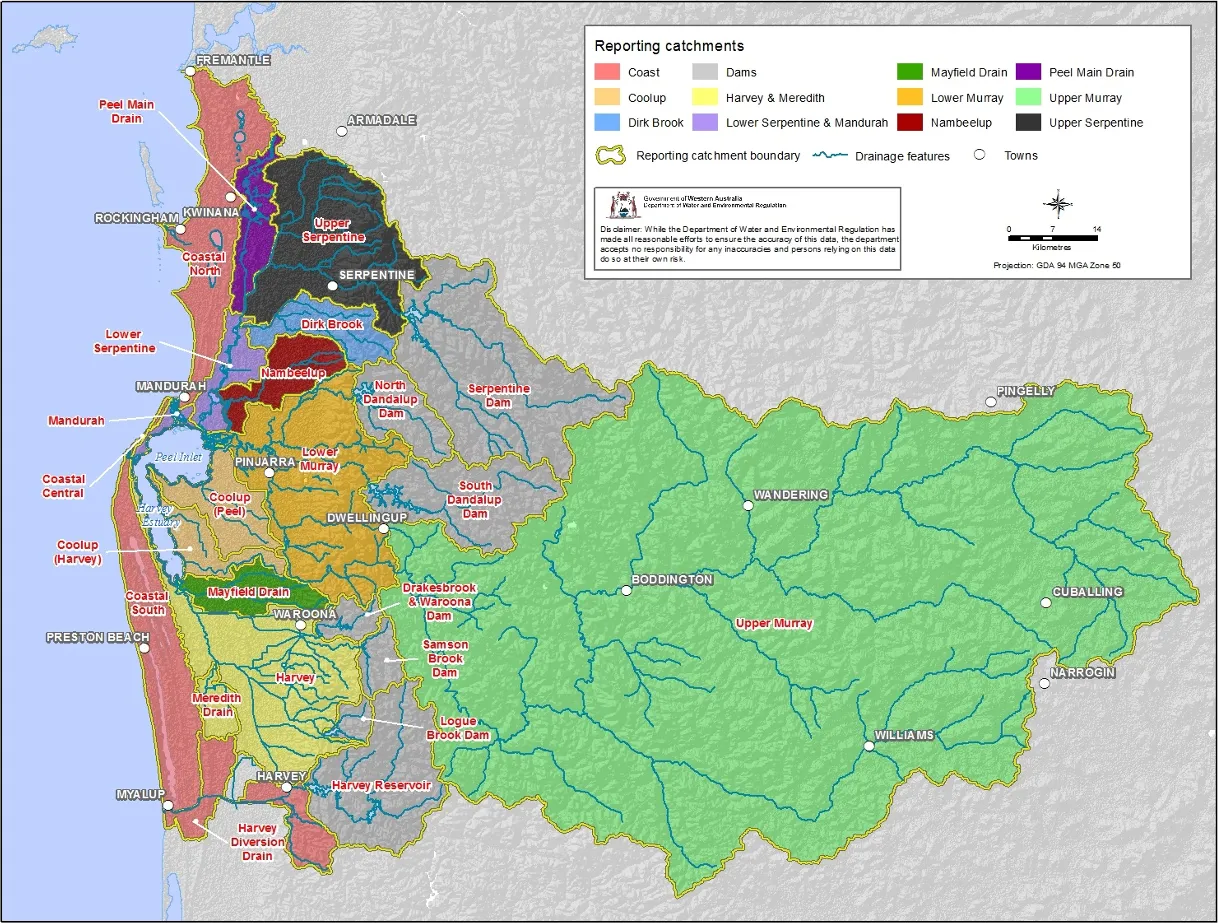

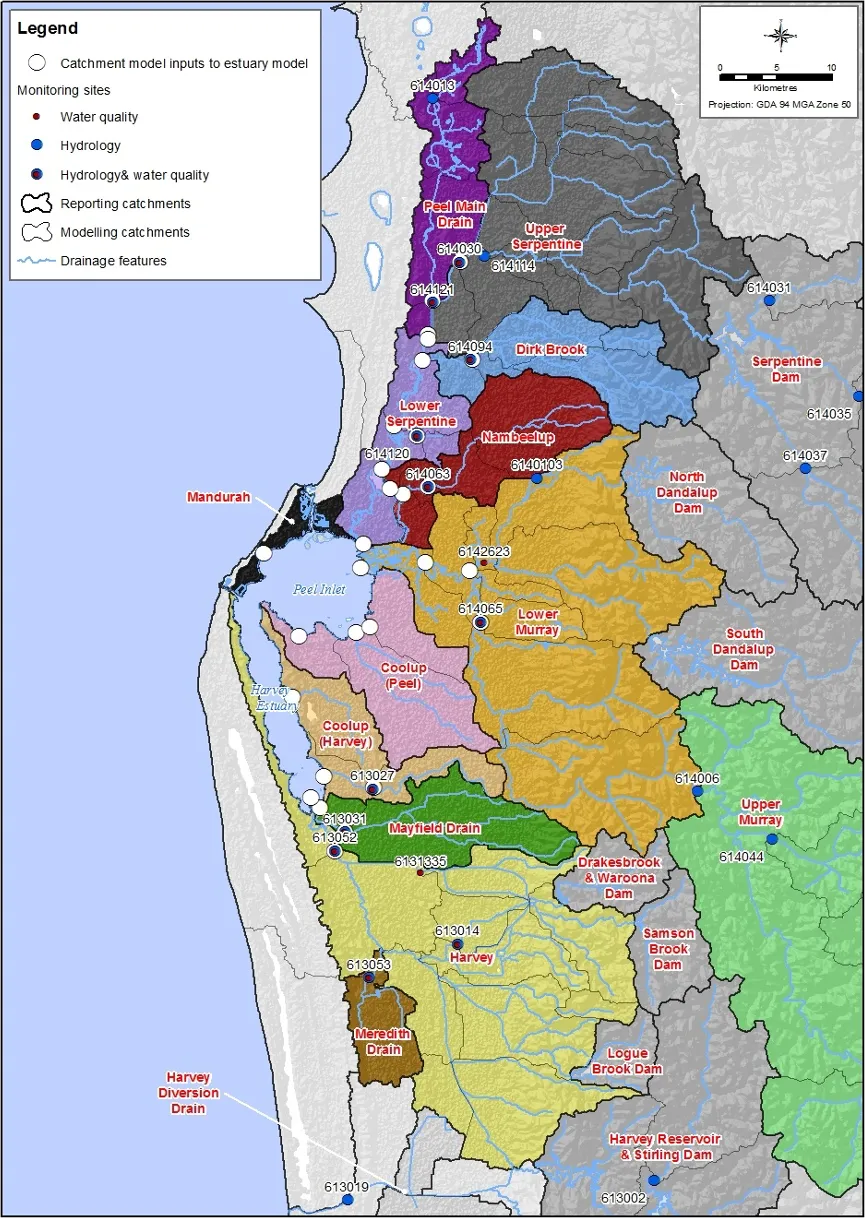

The Source (eWater®) modelling platform was used to develop hydrological and nutrient models for the catchment of the Peel-Harvey Estuary. These models allow the nutrient export delivered to the estuary to be estimated and the major sources of these nutrients to be identified. This allows management actions to be targeted where they will have the most capacity to reduce nutrient export.

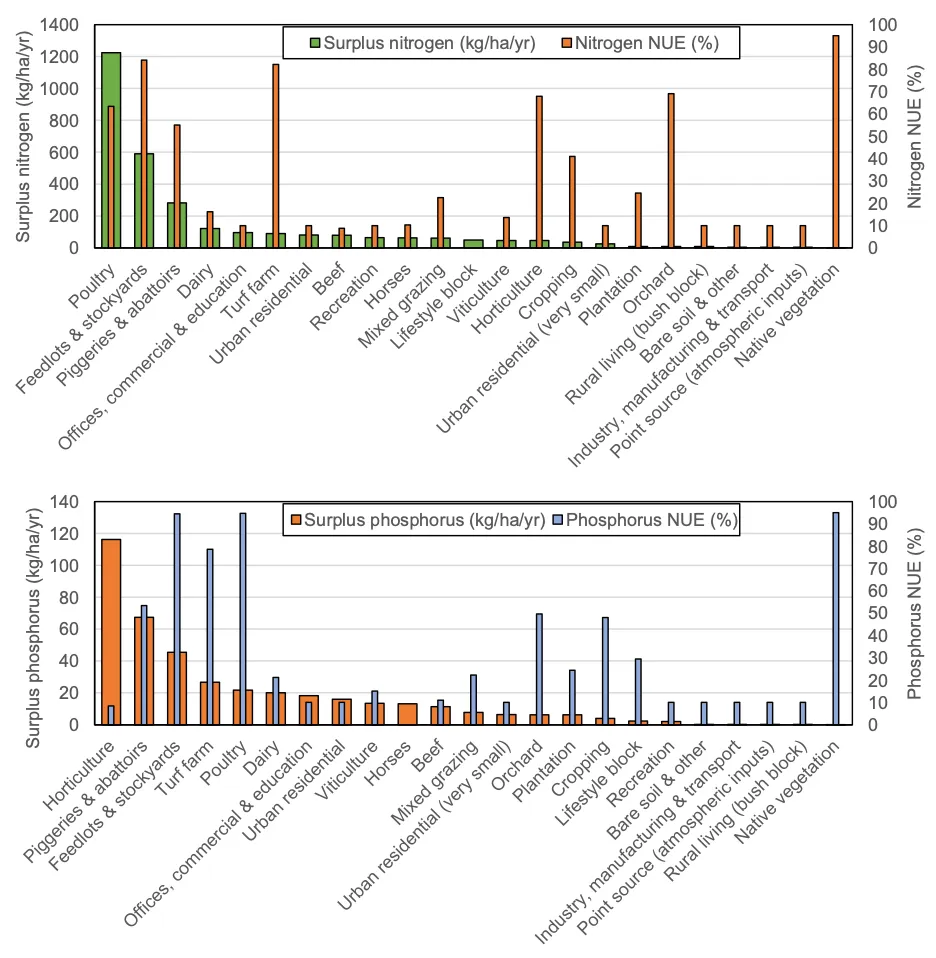

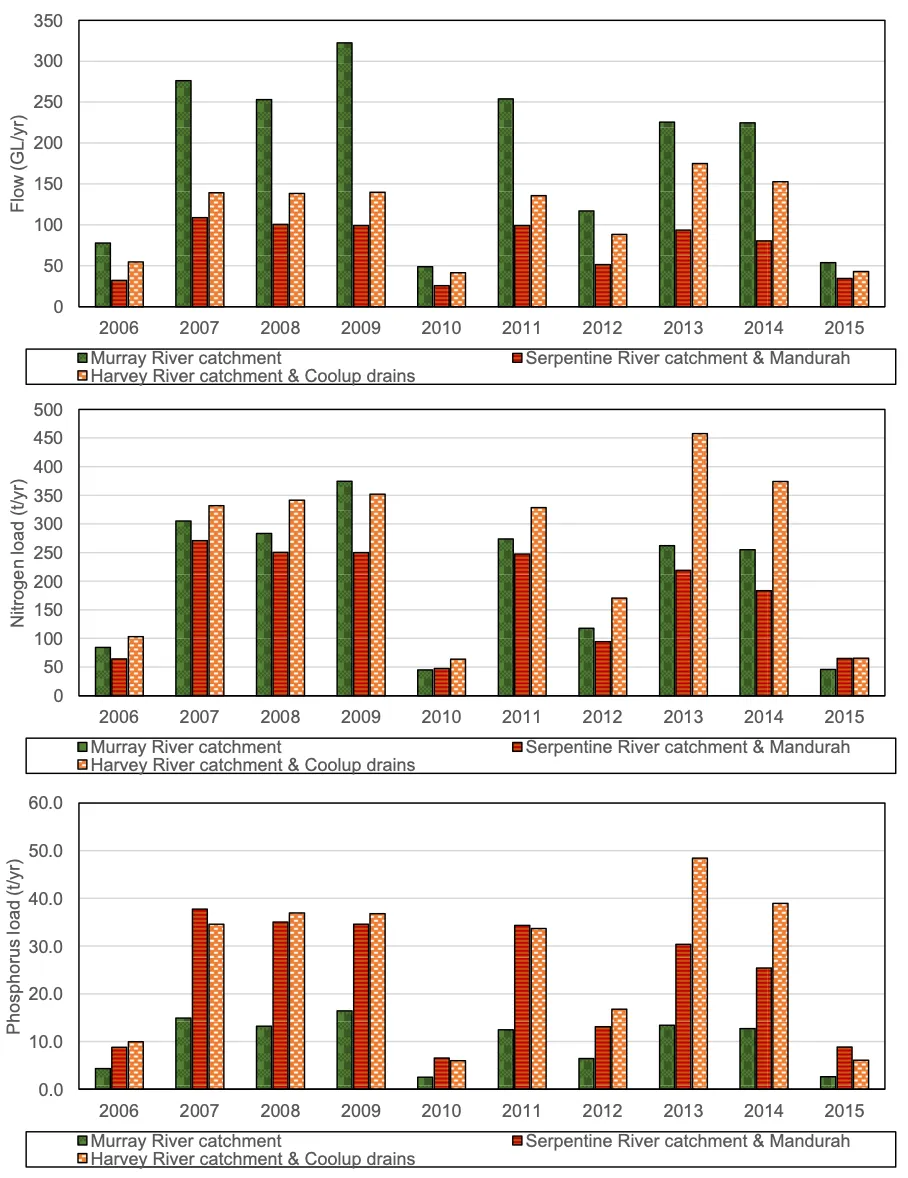

The model indicates that the nutrient load from all sub-catchments reaching the estuary is approximately 630 tonnes per year of nitrogen and 60 tonnes per year of phosphorus, averaged from 2006–2015. Additional nutrient loads also flow out to the ocean or are stored in dams. The major sources of nutrients by land-use are, for nitrogen, beef cattle farms (62% of total load), cropping (12%) and dairy cattle farms (6.8%) and, for phosphorus, beef cattle (67%), dairy cattle (8.1%) and horticulture (7.3%).

The catchment model, which was coupled with an estuary response model in subsequent aspects of the research, was then used to compare a range of scenarios proposed for 2050 by stakeholders across the Peel region. These scenarios encapsulated three different catchment management narratives (termed ‘environmentally optimistic, ’business as usual’ and ‘environmentally pessimistic/economically optimistic’) under two climate regimes (current climate and 2050 predicted climate). Full details of the catchment model development, calibration and outputs of the tested scenarios relating to (i) land-use change, (ii) nutrient management and (iii) climate are outlined in separate documents detailed in the following report.