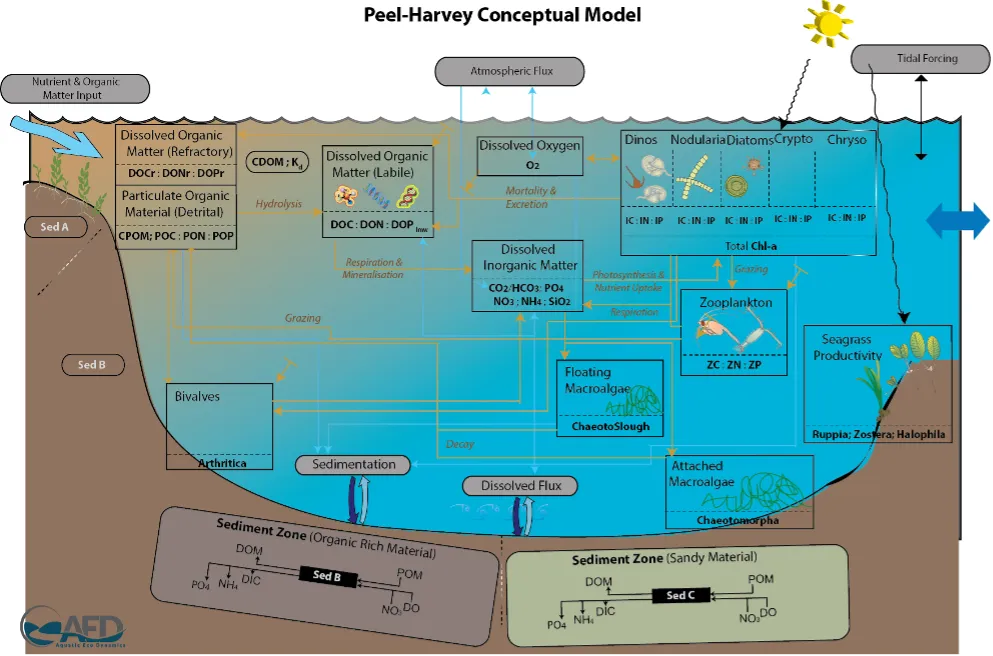

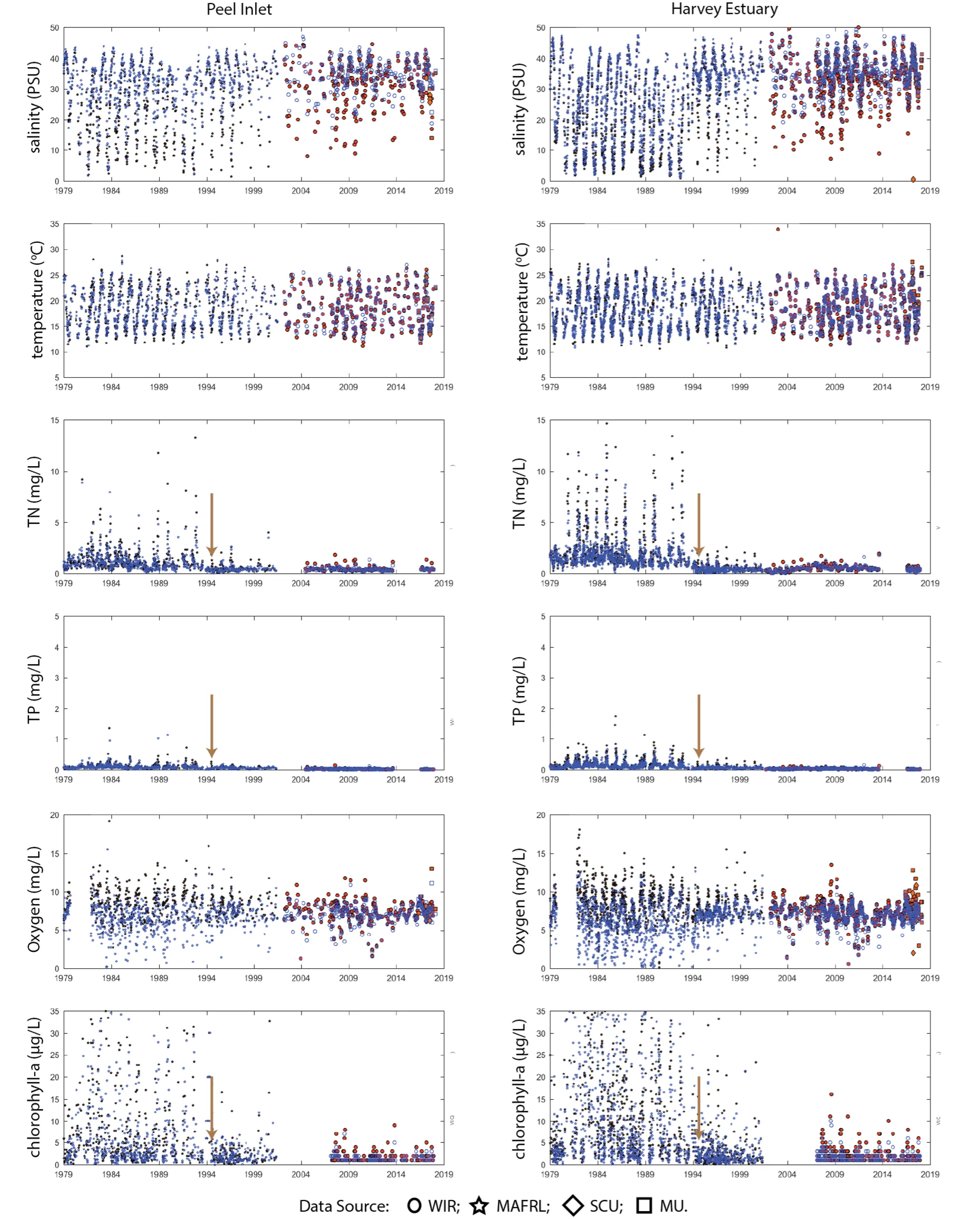

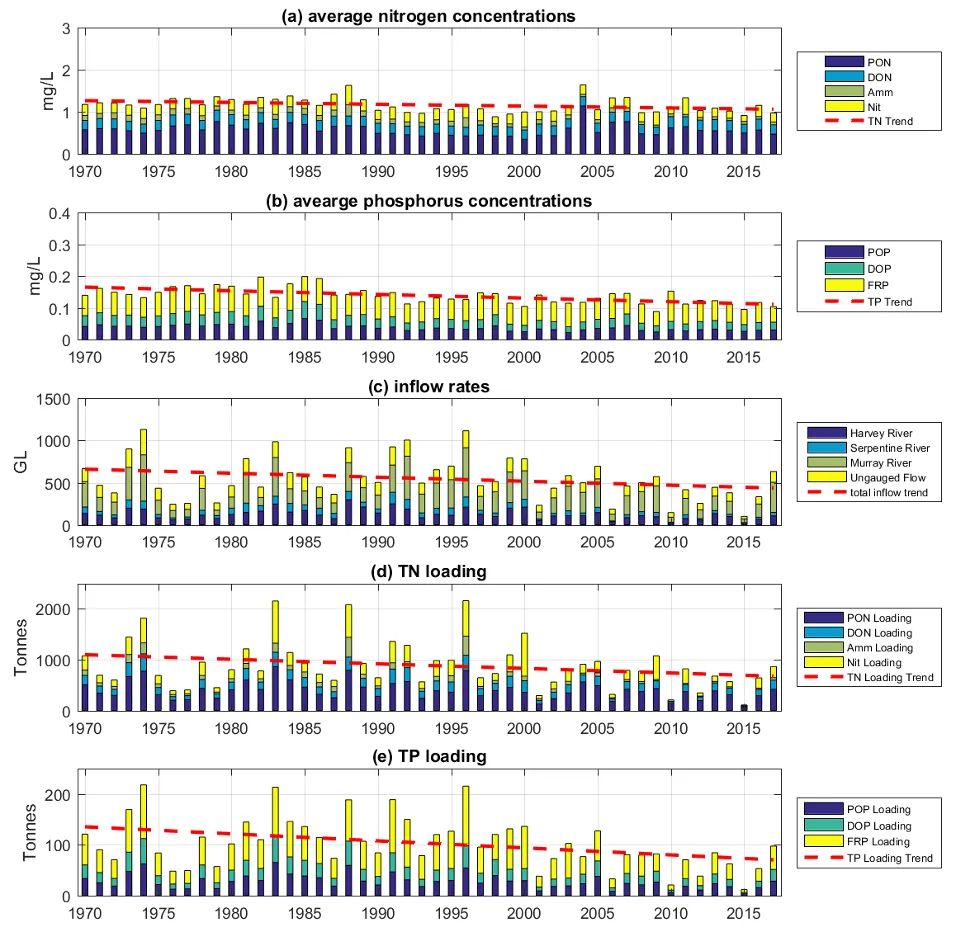

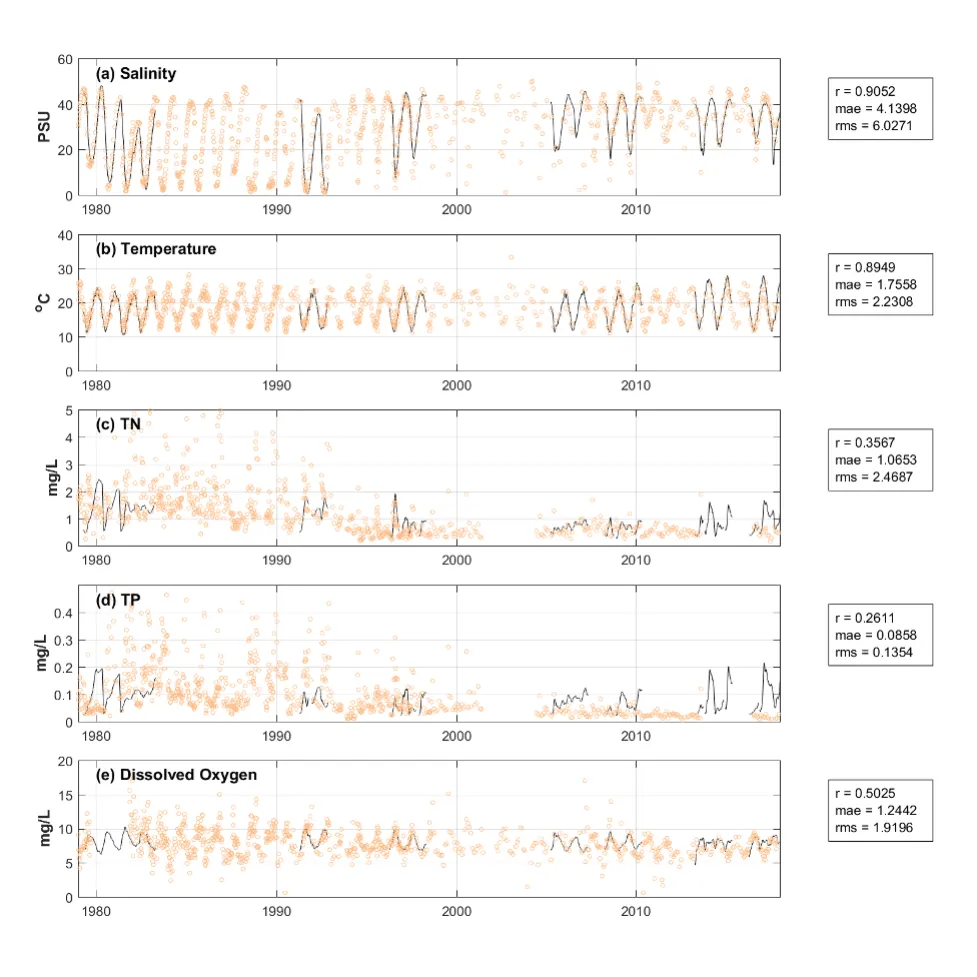

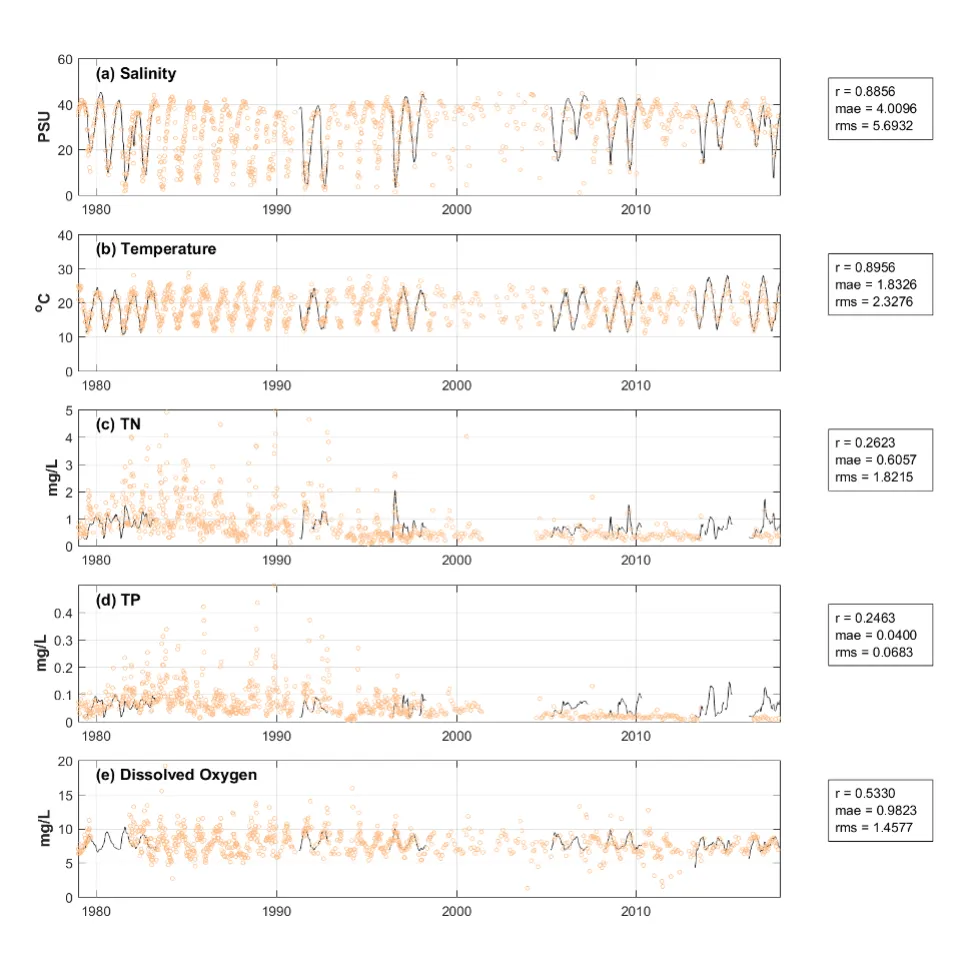

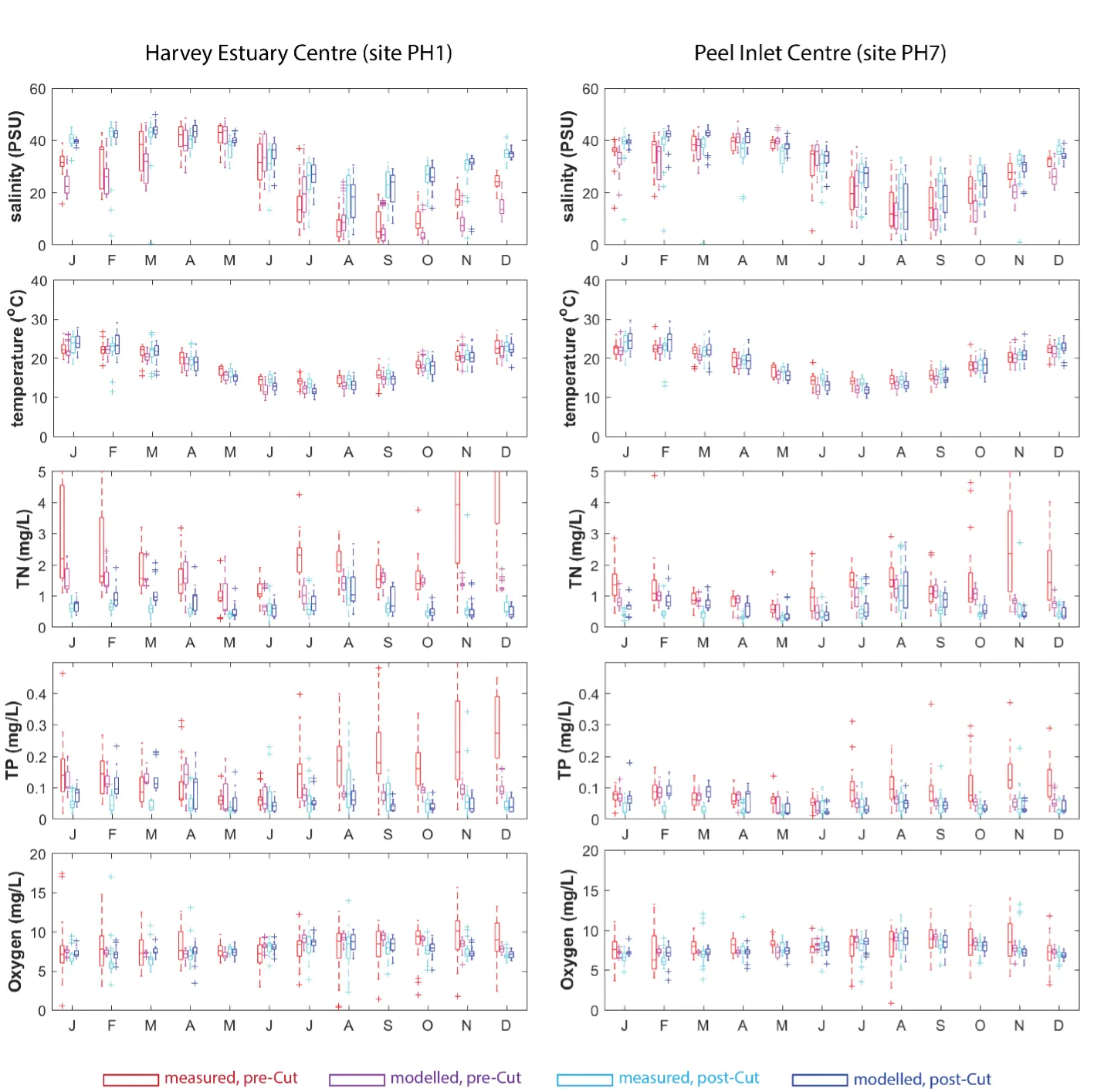

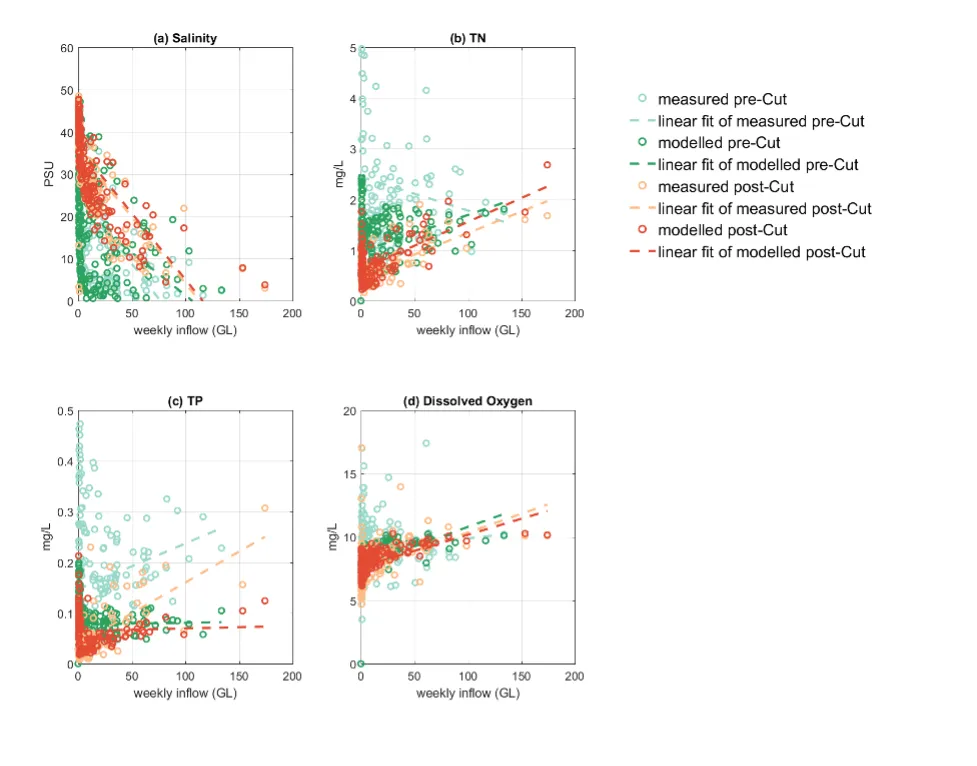

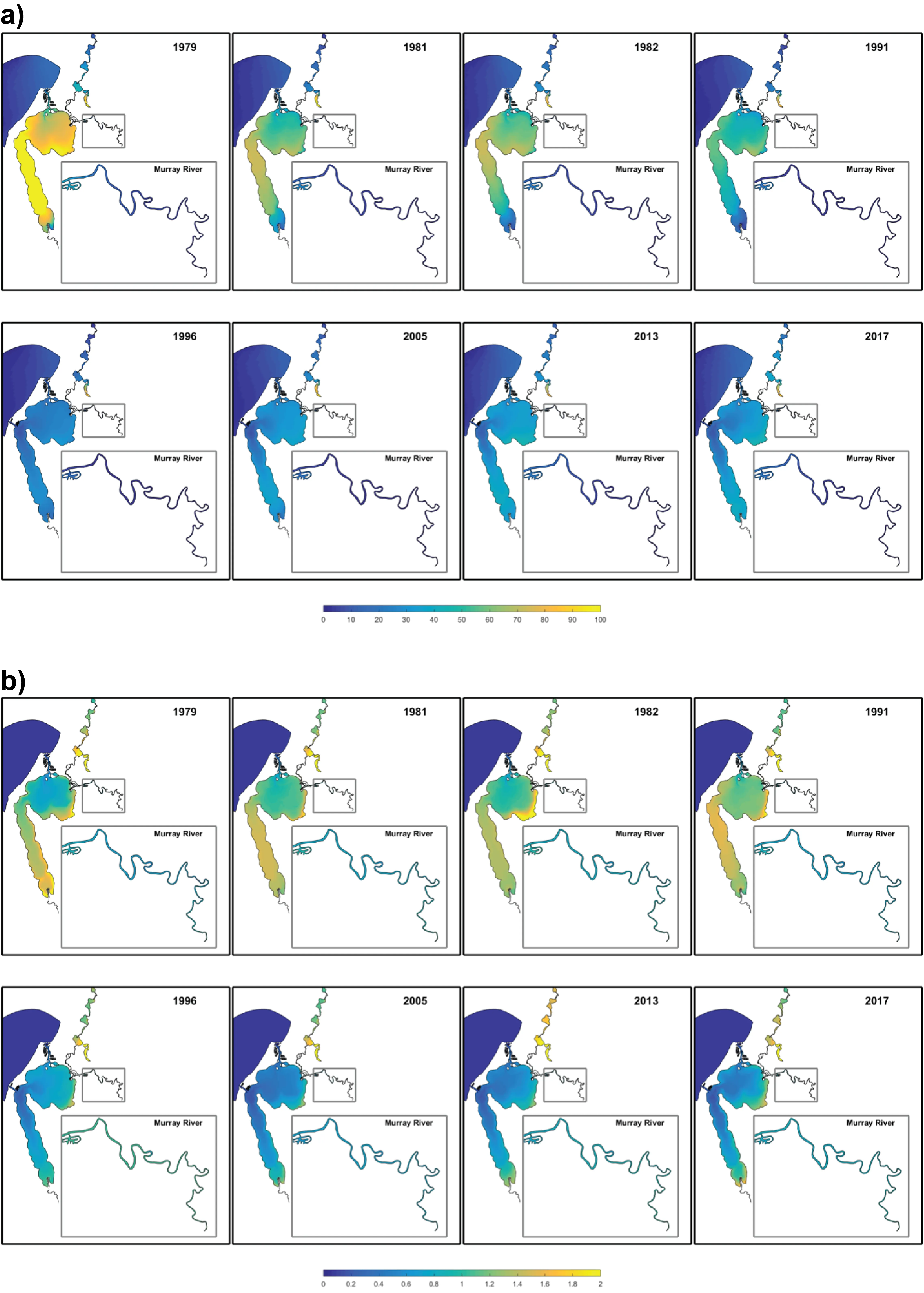

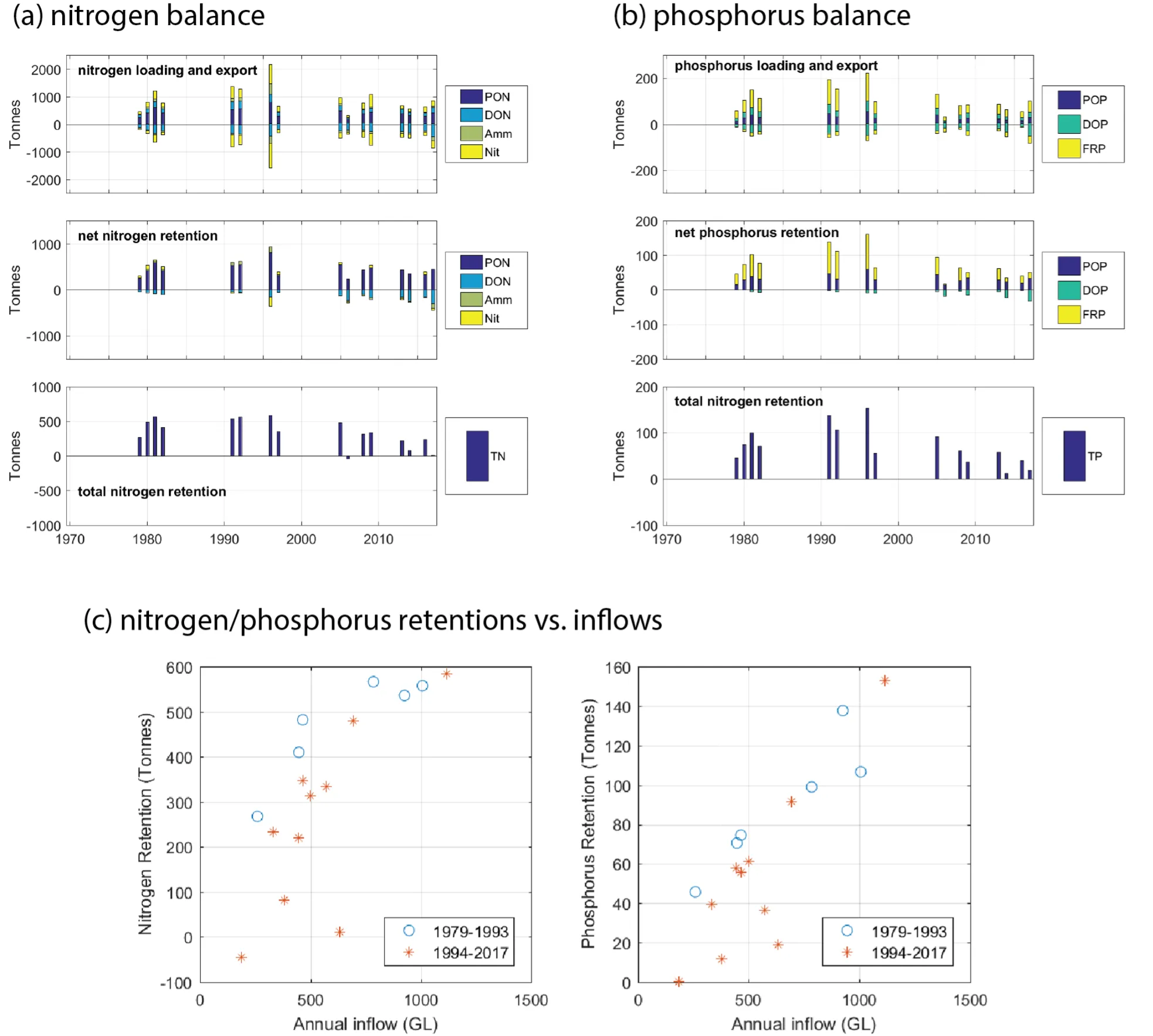

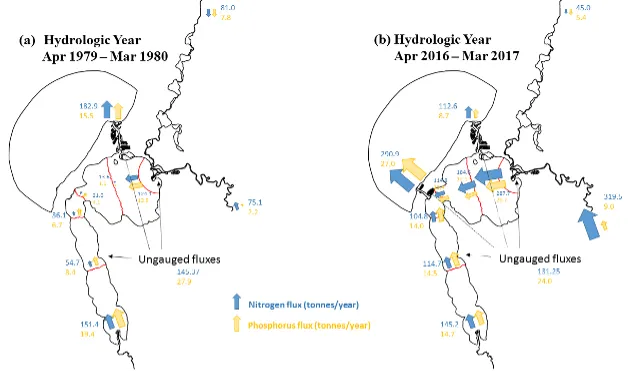

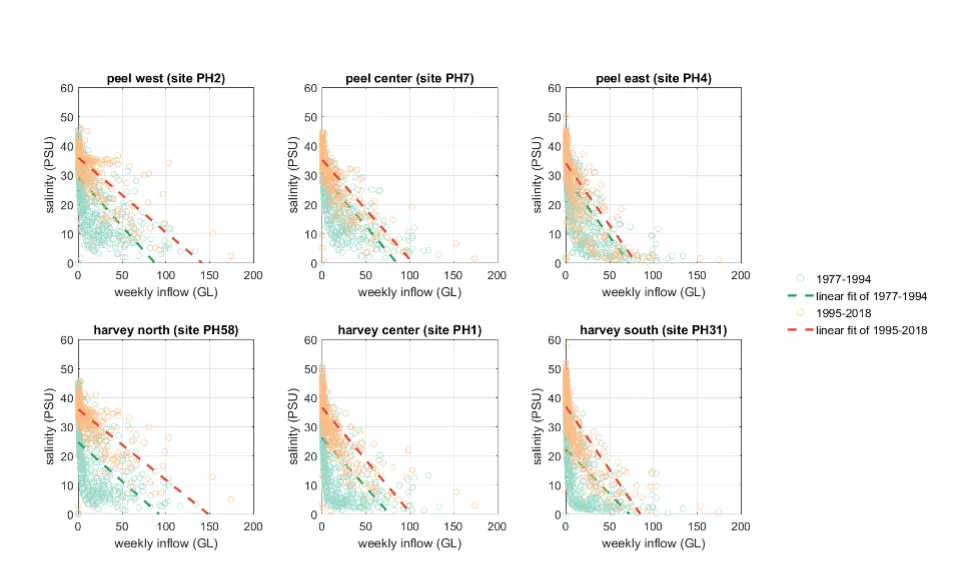

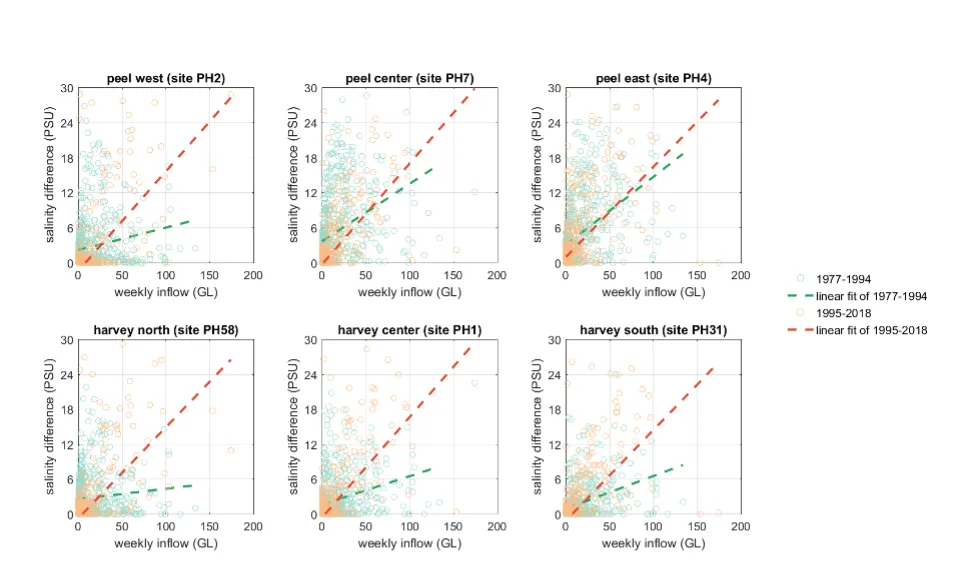

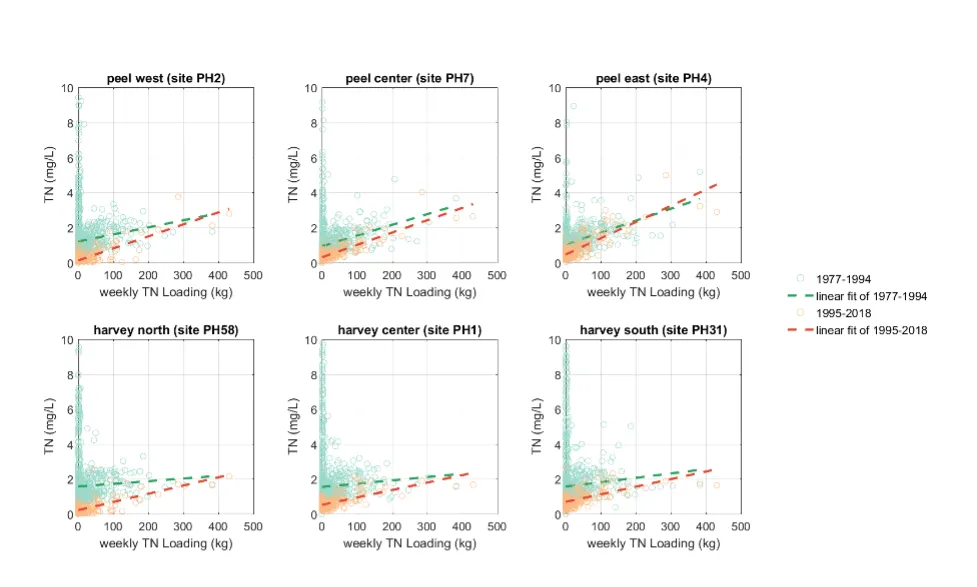

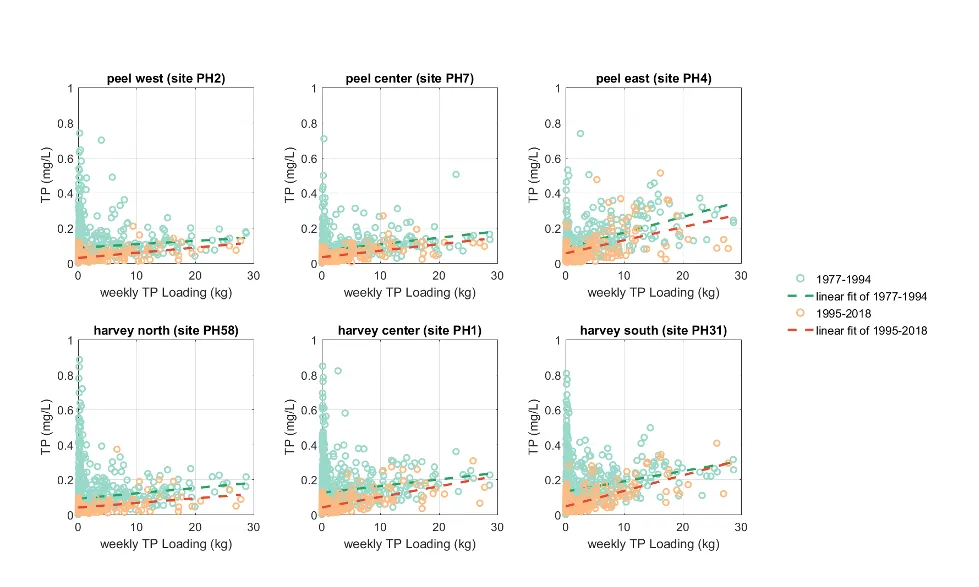

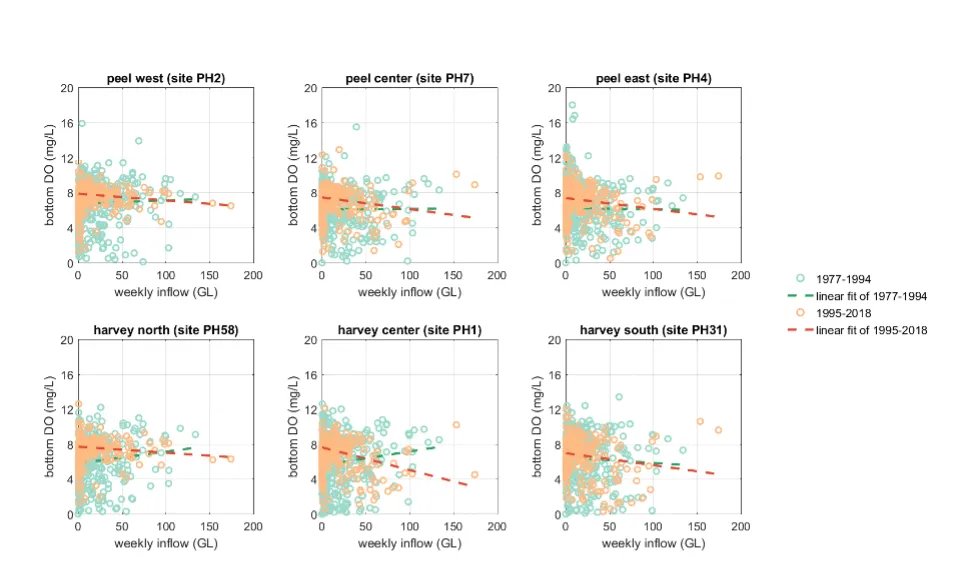

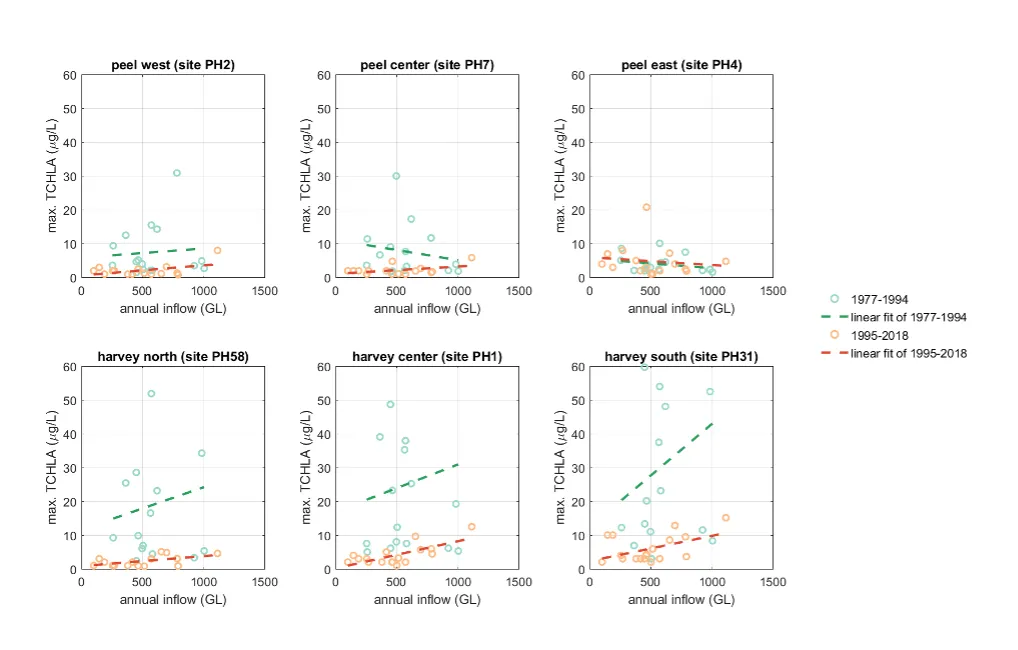

Long-term monitoring data (from 1970 to 2018) and 3D modelling investigations (of selected years from 1979 to 2018) were integrated to study changes in the water quality and nutrient budgets within the Peel-Harvey Estuary (PHE) in response to varied environmental stressors, including catchment loading, a drying climate trend, and the Dawesville Cut construction. The results showed that (1) there was a declining trend of nutrient inputs from the catchment into the PHE, driven by a reduction in flows and nutrient management measures in the catchment; (2) the role of the PHE system in filtering catchment nutrient inputs has changed due to the opening of the Dawesville Cut (e.g., addition of the Cut on average improved the TN export from 50% to 71%, and TP export from 31% to 49% of annual catchment loading, and the nutrient export via the Cut is about 2–3 times of that through the Mandurah Channel); (3) the PHE system has a significant spatial heterogeneity in water quality in response to catchment loading; (4) the estuary response model well reproduced the nutrient pools and water quality evolution in PHE especially in the post-Cut period, suggesting in its current form it is suitable for assessing management scenarios associated with nutrient load management or climate change; and (5) estuary response functions were developed to simplify models and showed locations near the channels are less sensitive to the catchment inputs, as well as that the Harvey Estuary displays a stronger salinity and phytoplankton biomass response to the catchment inputs compared to the Peel Inlet.

Key findings:

- A reconstruction of nutrient loads over time, including relative nutrient species partitioning, has shown the long-term reduction in load, but relative stability in flow-weighted inflow concentrations.

- Continual changes in water quality have occurred in the estuary over time, including following the Cut and as well as a long-term response following the reduced flows.

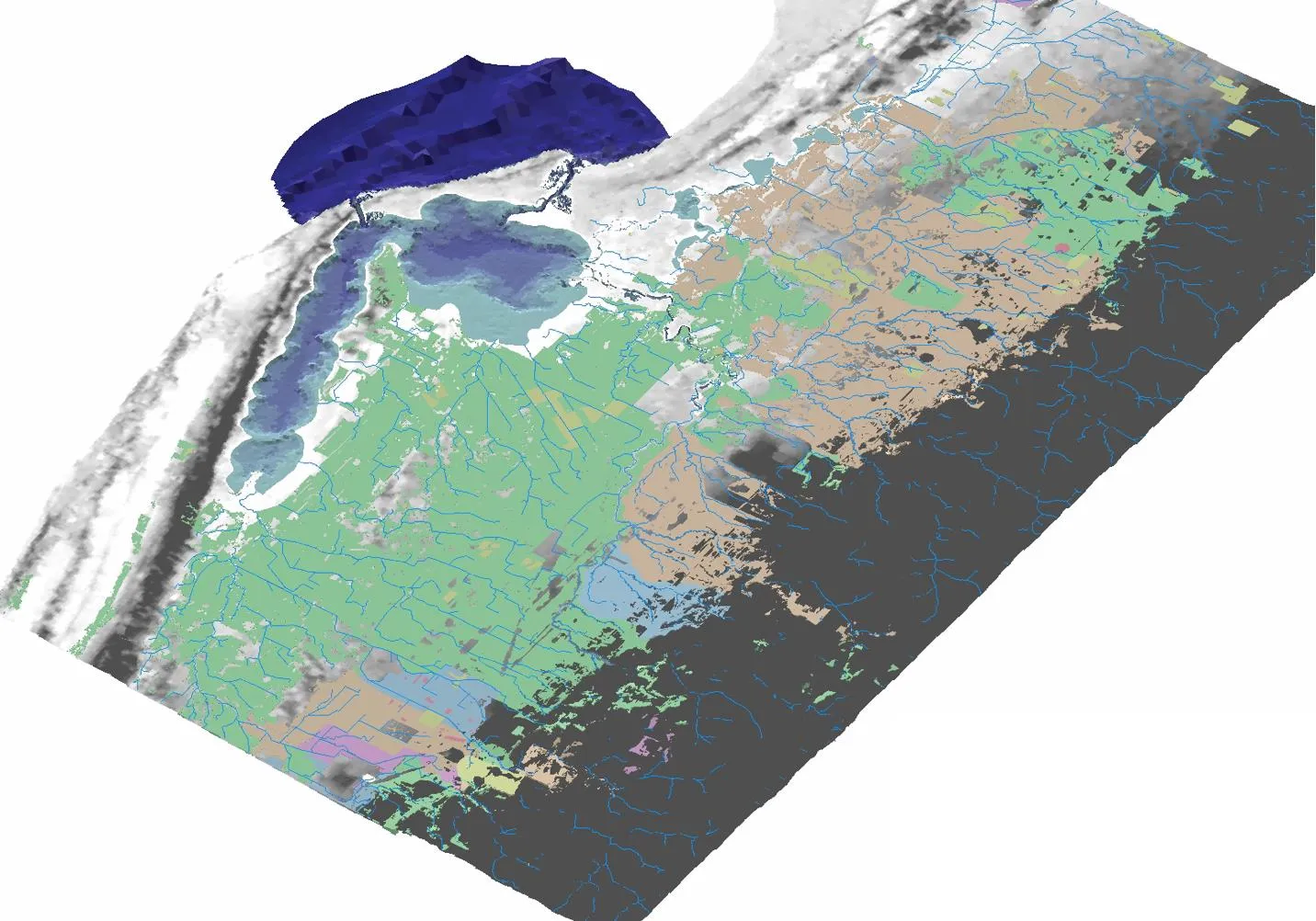

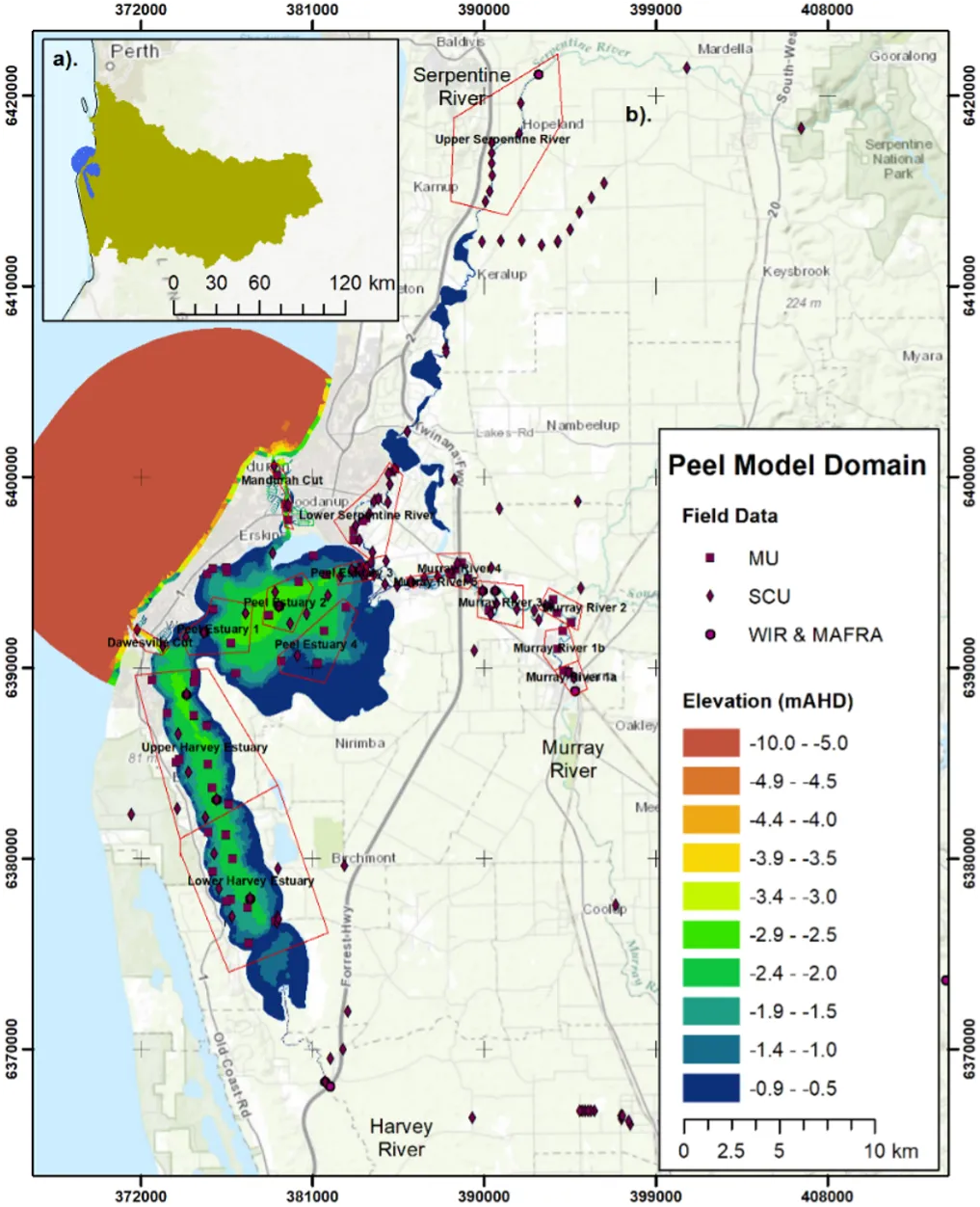

- The high-resolution Peel-Harvey Estuary Response Model has been able to capture water quality variability across regions from rivers to lagoons and channels.

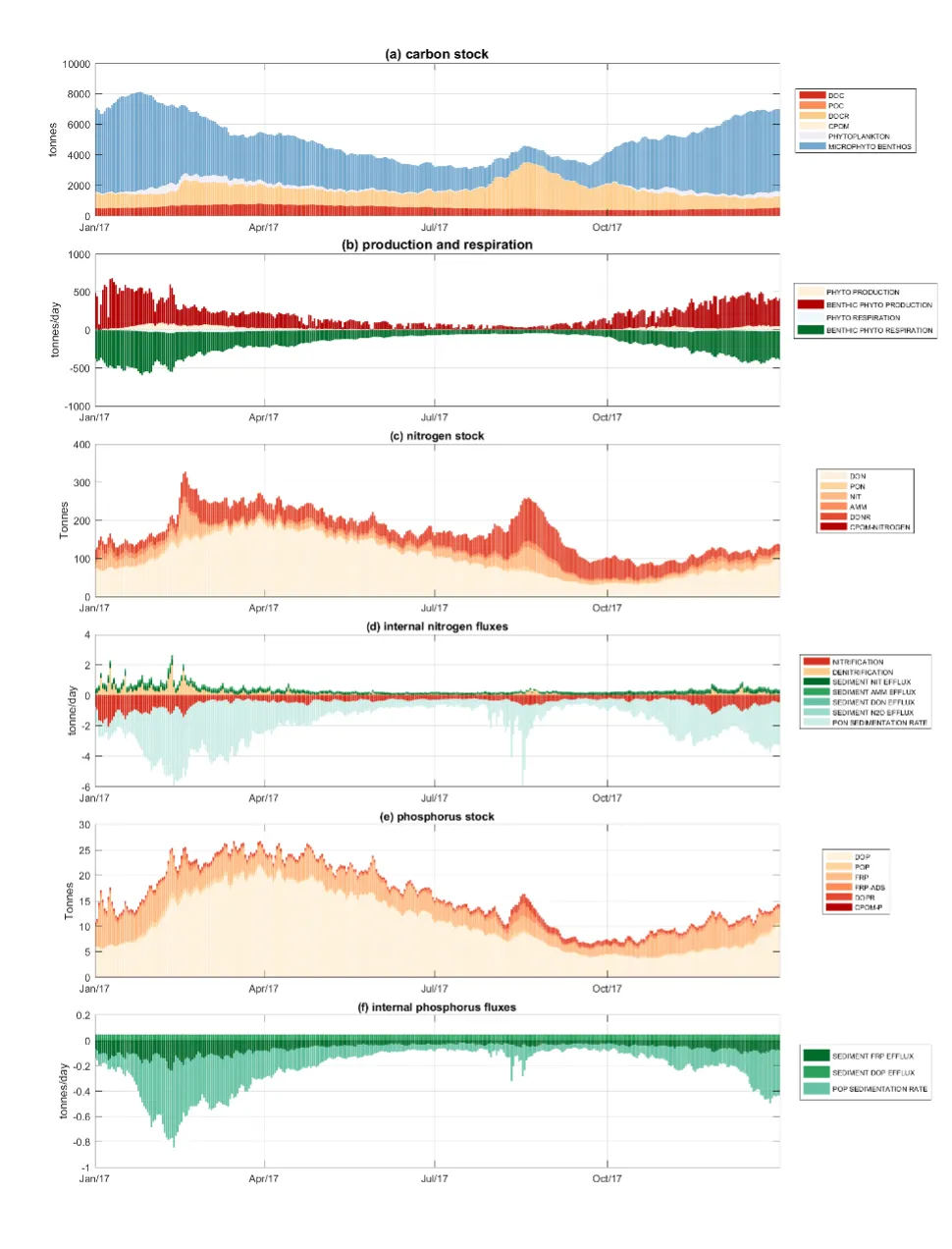

- The model has allowed the reconstruction of spatiotemporal variability in key water quality attributes and processes impacting the nutrient load partitioning within the estuary.

- Zonal budgets were undertaken to identify local controls on carbon and nutrient metabolism, and to determine how these respond to changes in flow and catchment loading.

- The pattern of retention and export has changed over time, following the Cut in particular, but recent changes also due to the reduced inflows.

- The amount of retention is dependent on annual flow, and therefore maybe sensitive to forecast projections due to drying climate.