Exercise 3A - Characterising soil moisture

this exercise you will measure some of the key properties for soil hydrology. To do this, you will collect soil from different locations of your choosing to analyse. You will then calculate soil moisture content, porosity and field capacity. Importantly, you will finish by thinking about the meaning of your results.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this exercise learners will be able to:

- Measure and compare key soil properties

- Interpret the implications of of soil properties for unsaturated zone hydrology.

Key terms in soil hydrology

Let’s start by remembering some key terms:

Porosity: The porosity is the ratio of the volume of the voids to the total volume of the sample. So if you have a sample of 100 cm3 and 30 cm3 is void space (non-solid), then you have a porosity of 0.3 or 30%.

Total Moisture Content: is measured by calculating mass loss during oven drying of wet samples at 103-105˚C for 1-2hrs. You can also measure the air-dried moisture content (measured as loss of mass during air-drying at a temperature of around 40˚C.

Saturated Water Content: Where all pore space in the soil is occupied by water and no further absorption of rainfall is possible. This will be equal to the total porosity.

Field capacity: The water content remaining after water has drained out of the soil under gravity. Technically, this is the moisture content remaining in soil subjected to -0.033MPa (0.3Bar) pressure (i.e. slight vacuum) because capillary action, osmotic pressure and gravity are balanced at this point. In the landscape, the excess water has moved downwared through the soil to become groundwater recharge.

Wilting Point: Plant roots can’t extract any more water (i.e. apply a suction stronger than -1.5 MPa) from this soil and begin to die. Permanent wilting point is the moisture content remaining in soil subjected to -1.50MPa (15 Bar) pressure (i.e. moderate vacuum).

Available Water Content: This is the amount moisture available for plants to extract, and is caluclated from Field Capacity – Permanent Wilting Point. This water does not drain through to the watertable under gravity, and also is not held too tightly by the soil, so that plants are able access it for uptake through their roots.Sample Collection

First, start by collecting your soil samples. After reading these instructions, be sure to make a list of everything you will need to take to the field so that you have everything you need.

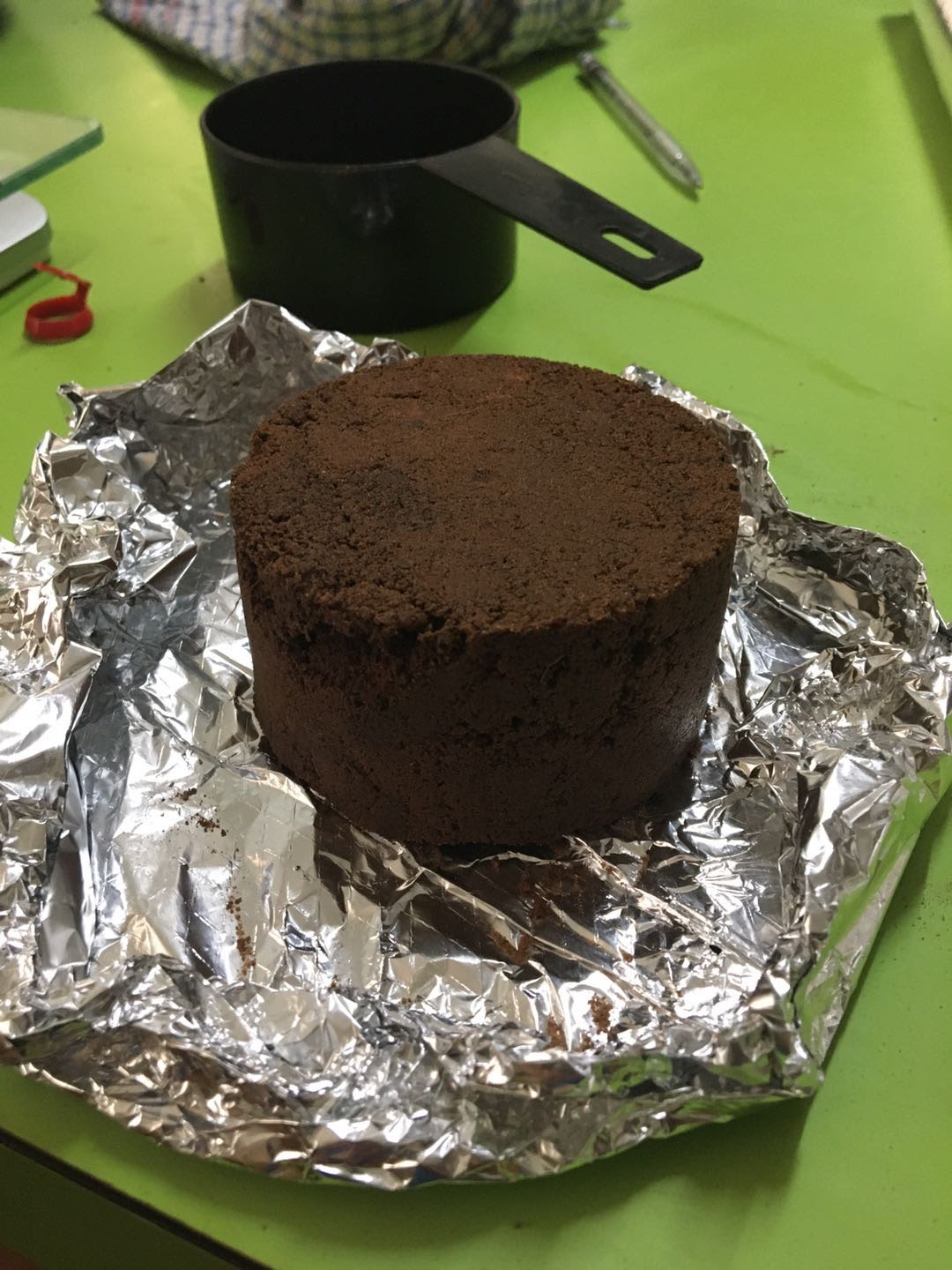

Find three locations nearby to you where you can easily access surface soil to a depth of 10cm. Using a trowel, clear the ground surface and use a small “core” (e.g. measuring cup or inverted can) to collect your samples. At each site you should collect three replicate samples. You will probably want to wrap these in foil to keep them from falling apart and then place them in a zip-lock bag (sealed tight to stop the sample drying out) with the sample ID recorded in permanent marker ready for transport back to “the lab” (i.e. your kitchen). While you are in the field make sure you record the coordinates (or location) where you collected the samples.

You should also make a brief description of the soil - what colour is it (in real scientific studies we use colour charts to make sure colour descriptions are robust and repeatable). Would you describe your soil sample as sand? Or is it silty, making it feel with finer grains because of the finer grains. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell just by touch whether a sample contains silt or clay because these are both fine-grained. To test for clay you can roll a sample in your palm, if it holds a cylindrical sausage shape then it contains clay. Does your sample seem to have a lot of dark brown organic matter, or not much?

For each sample use a kitchen balance to record the sample weight, making sure you correctly blank the balance to account for the sample container weight. Record the dimensions and volume of your samples. Then place them onto a tray that is suitable for going into the oven. Then place the tray into the oven for drying at ~105˚C. Leave in the oven until the sample is totally dry and then re-weigh (check after for 1-2 hours).

Now you can use your measured data to compute the soil moisture and porosity of each sample following the instructions below. Repeat for the three replicates of each soil and enter your sample details and your results into the online Google sheet.

A soil sample (core) collected using a kitchen measuring cup

Computing Soil Moisture and Soil Porosity

Soil moisture (water content) and porosity (proportion of void space) are key parameters that describe the capacity of soils to store water. Let’s calculate these parameters for each the the soil samples you collected.

Soil moisture: For each of your soils samples you should have measured the soil weight before and after drying in the oven. The mass-loss during oven drying represents the weight of water contained in that soil volume. (Note that clayey soils can retain considerable amounts of water when they are air-dry). Based on this water mass we can work out the gravimetric (by weight) and/or volumetric (by volume) water content of each soil sample. The volumetric water content (VWC, \(\theta\), theta, unitless because it is a ratio), is calculated from the mass of wet and oven dried samples and taking into account the total sample volume using Eq (8). You can express this value as a % by multiplying your result from (8) by 100. Enter your results into the online table (via Google Sheets)

Soil Porosity: Let’s now calculate the bulk density of the soil, and therefore the porosity of the soil. Bulk density \(\rho_b\) is the mass of dry soil per unit volume. You have already measured the dry volume of your soil, so to determine the bulk density you just need to work out the volume of your soil sample (if it was a column of core then volume = \(\pi r^2 h\) where \(r\) is radius and \(h\) is height of soil in the sample). From the bulk density and particle density \(\rho_p\) (2.65 g cm-3) you can then calculate the porosity \(\phi=\ \left(1-\frac{\rho_b}{\rho_p}\right)\). This value will also be a ratio, and you can multiply it by 100 to calculate the porosity as a %.

Now that you know the porosity, you can estimate the water storage potential, \(S_{\text{max}}\) of your sample by multiplying the soil volume by the porosity as shown in Eq (9). Add your results of these analyses to the online Google Sheet.

Estimating Field Capacity

Let’s now estimate the field capacity of our soils and see how that compares to porosity. To do this we need to wet our soils to field capacity by filling it with water (try placing it in a jug or bucket to wet the sample up and then letting the water drain out under gravity. You may need to secure the edges with foil (or similar) so that the core doesn’t collapse as it soaks, but make sure to allow for water to drain out the bottom.

Once all the drips have stopped, weigh your sample and then oven dry it and re-weigh to work out the volumetric water content of the sample at field capacity using Eq (8).

What did we learn?

Spatial heterogeneity is a substantial issue in subsurface hydrology. What is the variation between sample replicates? How does this compare to the mean of the measured values (i.e. is the variation large relative to the mean?). How much do the soil parameter estimates vary across the whole data set?

How did the volumetric water content in your soil compare to your estimate of the total porosity? Was the soil close to saturated, or very dry? Does this make sense in terms of where and when you collected it (time since rainfall, proximity to surface water or drainage).

Based on your measured Smax, what would be the water storing capacity in the upper 2 m of soil over an area of 1 km2 ? Does this seem like a lot of water, or not much?

How does your estimate of field capacity compare to your estimate of the total porosity? Does this seem reasonable? What does this mean for plant water availability?

What are the sources of error in your parameter estimates? What could you improve if you had to do this again?

What haven’t we measured that would also be useful to know about soils if we want to understand runoff and streamflow generation mechanisms?