Exercise 4 - Groundwater and surface water interaction

Learning Objectives

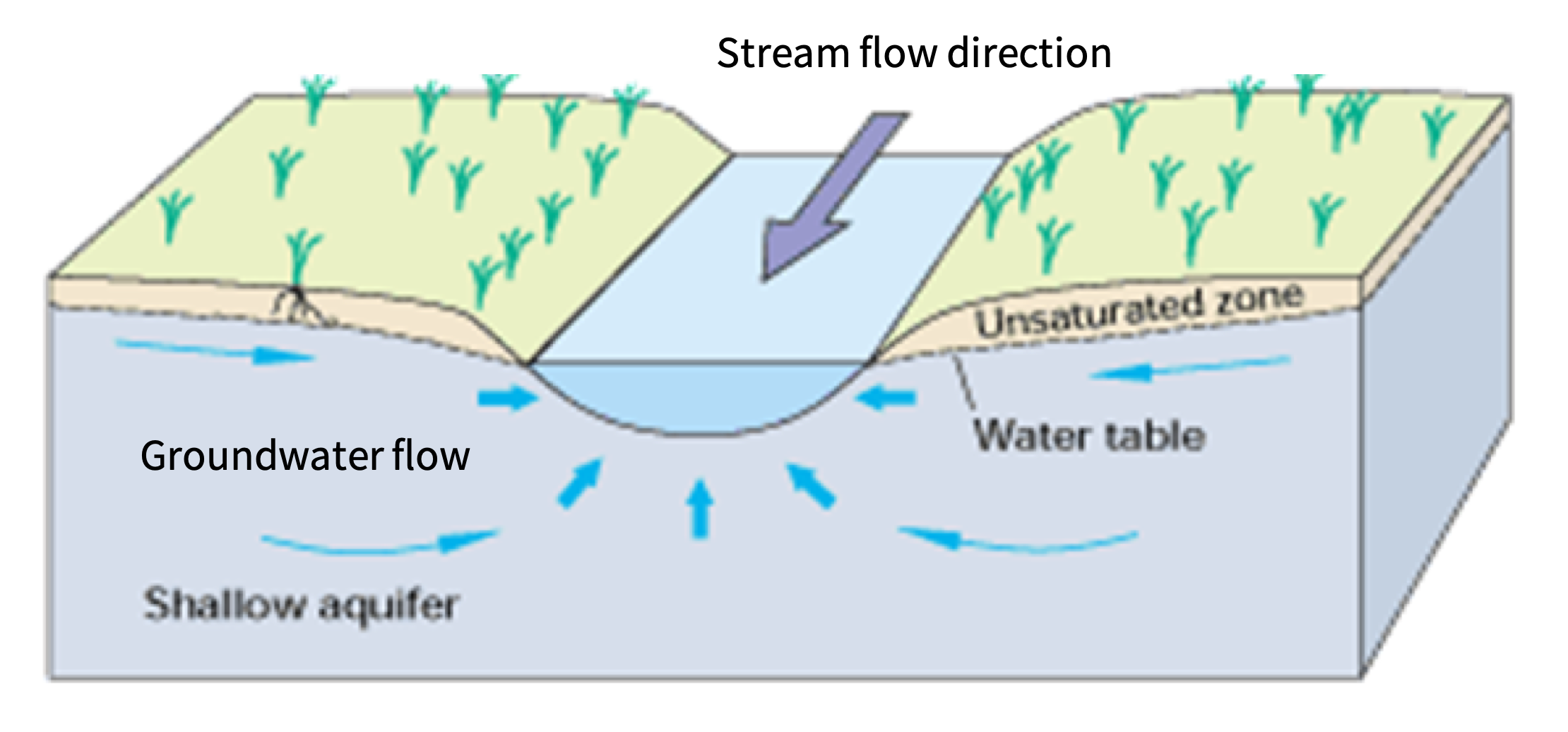

In this experiment, you will use data from a physical model of a catchment during a simulated rainfall event to calculate the relative contributions of pre-event and event water to that streamflow. The real-world setting for the experiment is a gaining stream (Figure 11).

At the conclusion of this exercise students will have demonstrated an ability to:

analyse measured experimental data to characterize the key properties of a rainfall event.

quantify pre-event and event components of water in a storm hydrograph (hydrochemical baseflow separation).

discuss the significance of experimental results for managing water resources in the context of surface water - groundwater interaction.

Background

A question we often want to be able to answer is how much groundwater is contributing to flow in a river, and how much is water that came from recent rainfall. This is relevant for water resources planning so we can work out the discharge rate of an aquifer, or for water quality management.

Figure 11: Groundwater discharge to a gaining stream.

Groundwater usually has different chemical characteristics to storm runoff during a rainfall event and we can use this chemical signal as a tracer for groundwater contribution. In this experiment you will demonstrate how groundwater (pre-event water) contribution to river flow changes over the course of a storm event, relative to water that fell as rain during the storm event (event water). You will use the tracer dilution technique with salinity (measured as electrical conductivity, EC) as the groundwater tracer.

Experimental Method

Set up of apparatus

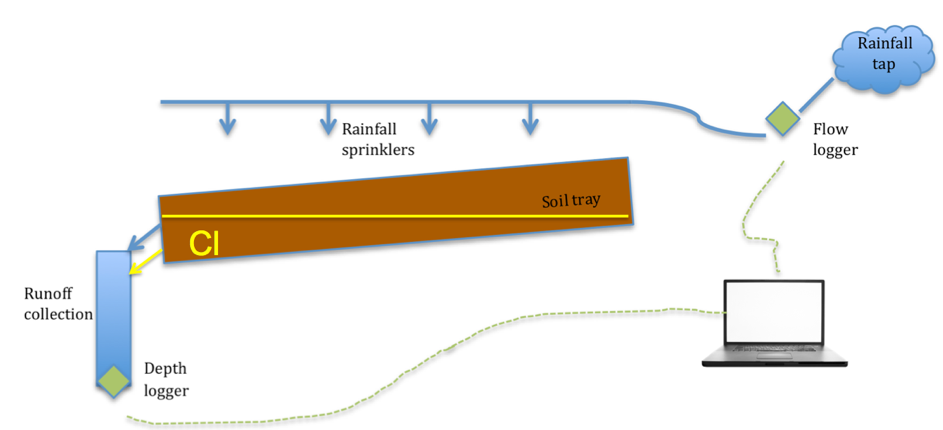

The experimental set-up consists of a tray of soil, the ability to add rainfall (via a connection to the tap) and discharge outlets at the bottom of the catchment. During the experiment loggers are set up to measure the rainfall amount as well as streamflow and EC at the catchment outlet over time (Figure 12).There are loggers for rainfall, streamflow and EC that are connected to a computer.

Figure 12: Experimental setup showing the catchment tray, rainfall, sprinklers and logger location.

Create the aquifer

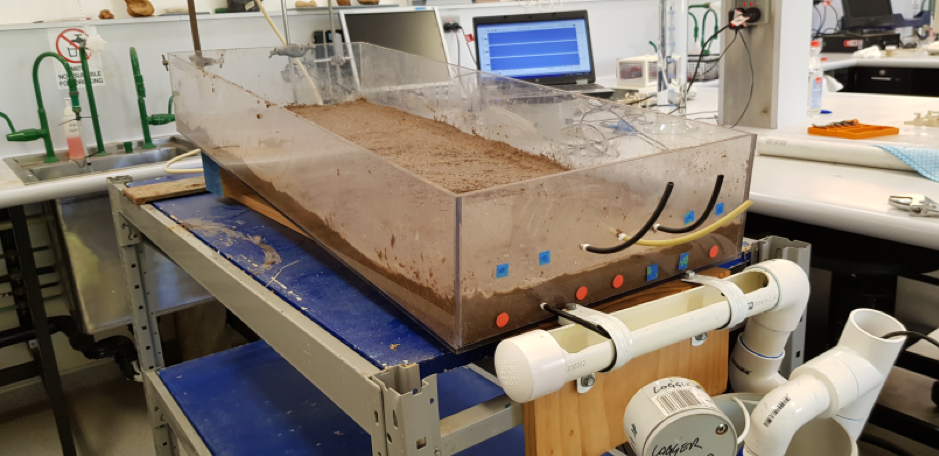

The first step was to create the “aquifer” by loading the bottom of the tray with river sand. The top surface was smoothed so that it was an even thickness across the catchment and then the volume of this layer was estmated. Importantly, the top of aquifer sits below the top line of outlets as shown in Figure 13. A core to sample of the soil was collected so that you can compute the starting soil moisture (refer to Exercise 3A for the methodology to do this). To create the pre-event groundwater, the sand was saturated with saline water (making sure to note the EC of the saline solution) and any excess ponded water removed with a syringe before proceeding.

Figure 13: Saturated aquifer correctly set up within catchment model.

Create the unsaturated zone

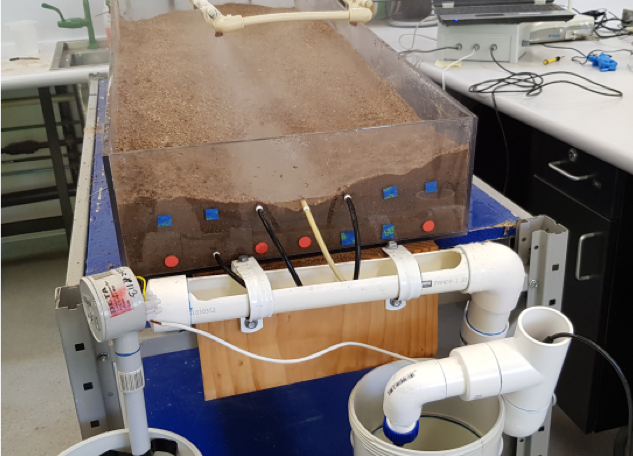

This saturated aquifer layer was then overlain with a second layer of dry soil, being careful not to disturb the original layer. This upper layer was shaped into the form of a catchment (concave) so that when the subsurface fills up there was a stream flowing to the catchment outlet (Figure 14). The middle outlet should not be covered with soil, but the soil should be just below this outlet (this is your riverbed). At this step you could see some capillary rise of aquifer water into the vadose zone.

Figure 14: Unsaturated zone on to of aquifer. Topography should slope towards the middle and the catchment outlet.

Make it rain

The rainfall outlets were brought close to the catchment surface to avoid “raining” outside the catchment, and then the tubes at the bottom of the catchment were turned so that they were directed into the PVC drain so that outflow could be measured. And now the rain! The apparatus was left with the rain on for approximately 20 minutes until the catchment had filled up, stream flow had begun and the EC at the catchment outlet has clearly decreased (Figure 15). To finish, the rain was turned off, but with the loggers still running for another 20 minutes, or until streamflow ceased, so we could measure what happens after the rain had stopped.

Figure 15: Streamflow at the catchment outlet.

Data Analysis

QA-QC of data

Download the data provided.

Before you can start your analysis you might need to clean the data – remove any outliers and identify where your experimental data start and stop. You have very high temporal resolution data, which combines with the sensitivity of your loggers to give you a lot of noise. Consider calculating a running average (over 60 seconds or more) to get smooth temporal trends.

Characterizing the rainfall event

Once you are happy with your clean data set you can use the logged data to identify the properties of the storm event, including:

- Time from rainfall onset to when runoff began to be recorded (mins),

- Time to peak discharge (mins),

- Total rainfall volume (cm3),

- Total runoff volume (cm3),

- Average rainfall intensity (cm/min),

- The runoff coefficient, \(c\), for the ‘storm’ event.

Separating pre-event and event water

Now let’s calculate the contributions of pre-event (baseflow = groundwater) and event (rainfall and runoff) water. Because the groundwater was saline you can use the tracer dilution method (see the blue box below for details) to calculate the fraction of the hydrograph that is from baseflow. In other words, we want to calculate and plot a hydrograph showing each of the components of the water balance:

\(Q_{\text{out}}(t) = Q_{\text{event}} + Q_{\text{pre-event}}\)

where \(Q_{\text{out}}\) (cm3/s) is the volumetric flow rate measured at the outlet of the catchment, \(Q_{\text{event}}\) (cm3/s) is the volumetric flow rate of event water (representing rainfall and runoff) and \(Q_{\text{pre-event}}\) is the volumetric flow rate of pre-event water (representing groundwater).

If there is a difference in the salinity of groundwater and rainfall-runoff then we can estimate the groundwater contribution to the streamflow by looking at changes in salinity at the catchment outlet (measured as electrical conductivity, or EC).

To do this we assume that the EC in groundwater is at a pre-event reference level, \(S_{\text{pre-event}}\), and EC in the rain \(S_{\text{event}}\) is effectively 0. The level of dilution in EC in streamflow can then be used to estimate the fraction of pre-event (groundwater baseflow) and event (rainfall-runoff) water contributing to total streamflow.

The salt mass balance tells us that the total salt mass coming out of the catchment via the stream must equal the sum of pre-event and event components:And because the rainfall and runoff didn’t have any salt added, \(S_{\text{event}} = 0\)

So that we can cancel the “event” term and rearrange to solve for the pre-event component of volumetric flow:Interpretation and conclusions

How do the relative amounts of pre-event and event water change over time? Is the change in \(Q_{\text{pre-event}}/Q_{\text{event}}\) over time what you would expect?

How could attributes of the experimental setup have increased or decreased the baseflow contribution?

How would the results have changed if we ran the experiment again, starting with a wetted-up unsaturated zone?

How realistic is the experiment in terms of capturing the interaction of surface water and groundwater?

What are the significance of these results for water resource management?